Keep Condorcet in Consideration as an Electoral Reform Option

It’s wrong to argue that Condorcet Voting should be rejected entirely and everywhere.

It’s nice to see that there is emerging a healthy debate within the election reform community on the relative merits of Instant Runoff Voting (IRV) versus Condorcet-consistent electoral methods. Since 2000 until relatively recently, IRV has been the dominant electoral reform proposal in the United States. It gained its preeminent status as a response to “the spoiler effect” that was glaringly apparent when Al Gore lost the 2000 presidential election to George W. Bush because Ralph Nader was also on the ballot and there was no instant runoff to show that with Nader eliminated from the race Gore would have prevailed over Bush.

Lately, however, several scholars—myself included—have been arguing that solving the spoiler effect is not the only task necessary for electoral reform. Instead, the problem of polarization creates a “center squeeze” in which a candidate preferred by a majority of voters when considered head-to-head against either a candidate on the left or a candidate on the right cannot prevail. Polarization causes a faction of the electorate, although not a majority, to enthusiastically prefer the left over the center and the right, and an opposing faction, although not a majority, to prefer the right over the center and the left.

Under the prevailing plurality-winner electoral system, in which all that matters is winning more votes than any other candidate, a polarized electorate will yield either the left or the right as the winner even though a majority of voters would have preferred the center to win. Sometimes, it will be the left that wins, and sometimes the right. Either way, a majority of voters will be dissatisfied. It is this repeated frustration of what the majority wants, as the left and right move further and further apart under conditions of increasing polarization, that is causing such a crisis of confidence in the capacity of democracy to deliver government on behalf of the citizenry.

IRV isn’t designed to deal with this problem. Its procedure is to eliminate the candidate with the least enthusiastic support, causing the election to end up a battle between the two candidates with the most enthusiasm behind them. Consequently, when a polarized electorate is divided between enthusiastic supporters of candidates on the left and right, with fewer voters viewing as their favorite candidate a centrist who’s a solid second choice for both the left and the right, IRV drops the centrist candidate from contention, making the race end up a polarized choice between left and right.

This attribute of IRV has caused scholars who are concerned about the deleterious effect of polarization on democracy to consider the possibility of a Condorcet-consistent voting system instead of IRV. A Condorcet-consistent voting system, named after the French mathematician who developed the idea, will always elect any candidate whom a majority of voters prefer compared head-to-head to each other candidate. A Condorcet-consistent system is thus well-suited to deal with the problem of polarization because it will elect the centrist whose own supporters plus voters on the left prefer to the polarizing candidate on the right and whose own supporters plus voters on the right prefer to the polarizing candidate on the left.

I, for one, came to embrace the idea of pursuing Condorcet-based electoral reform only after realizing that IRV is unlikely to be adequate to the task of curing what ails American democracy. I saw rule-of-law Republicans, like Senators Rob Portman of Ohio and Richard Burr of North Carolina, being increasingly replaced by right-wing MAGA election deniers like J.D. Vance and Ted Budd. This replacement wasn’t because a majority of the state’s voters preferred the MAGA election deniers to the rule-of-law Republicans. On the contrary, it was because the existing electoral system wouldn’t let the majority’s preference prevail.

I had hoped that eliminating partisan primaries would be enough to solve this problem. Alaska’s system, with its nonpartisan primary in which all candidates regardless of party affiliation compete to be one of four finalists who advance to the general election where IRV is used to pick the winner, seemed to me a ready-made solution that would let rule-of-law Republicans like Portman and Burr compete against election deniers like Vance and Budd without the need to win a MAGA-dominated partisan primary. But after studying the issue (as an election law scholar should do), I realized that given the nature of polarization in states like Ohio and North Carolina, rule-of-law Republicans like Portman and Burr couldn’t win an IRV general election. They would be dropped by the IRV process, and the election deniers like Vance and Budd would win the IRV general election just as they would win in the existing electoral system.

The victory of the election deniers in an IRV election is no more democratic than in a plurality-winner election. Either way, it is still true that a majority of the state’s voters would prefer to elect the rule-of-law Republican instead of the election deniers. Only a Condorcet-consistent electoral system would enable the will of the majority to prevail and elect the rule-of-law Republican instead of the election deniers. Accordingly, based on this analysis, I began to advocate for consideration of Condorcet-consistent voting methods as an alternative to IRV. And I’m by no means the only one, with others doing so for similar reasons.

This recent scholarly advocacy of Condorcet voting has caused adherents of IRV to push back. For example, Greg Dennis, who is affiliated with a Massachusetts organization devoted to pursuing the adoption of IRV, has written a Substack essay arguing that IRV is “superior to Condorcet Voting as a tool for political depolarization.” (Dennis uses the term “Ranked Choice Voting” instead of IRV, but I consider that usage confusing since IRV is but one specific version of voting with ranked-choice ballots, and indeed Condorcet Voting can be conducted with ranked-choice ballots although it also can be conducted with ballots that enable voters to make the necessary head-to-head comparisons directly.) Dennis’s piece is thoughtful, well-written, and worth considering. It also acknowledges that the concept of Condorcet Voting has inherent “mathematical appeal” precisely because it “guarantees” the election of any candidate “who beats every other candidate” when each pair of candidates is compared head-to-head. But Dennis argues against any effort to adopt Condorcet Voting in practice and sticks instead with his organization’s goal of adopting IRV, for two reasons. Because I view both of these reasons as unpersuasive, I want to explain here why neither justifies abandoning serious consideration of Condorcet Voting as an alternative to IRV to redress the problem of polarization.

First, Dennis contends that it’s unnecessary to pursue Condorcet Voting as a substitute for IRV because in practice IRV will elect the same candidate as Condorcet Voting virtually all of the time. In making this point, Dennis relies on a paper by Nick Stephanopoulos showing that in over 99% of actual elections where IRV has been used the winner is the same candidate who would have won if a Condorcet-consistent method had been used to tabulate the result from the same set of ballots. But this statistic cannot settle the question whether or not Condorcet Voting is necessary to adopt instead of IRV to combat polarization for a key reason that Stephanopoulos acknowledges at the end of his paper: an electoral system with IRV, like a plurality-winner electoral system, may cause a candidate who would win a Condorcet-based election to refrain from competing because there is no point doing so. As Stephanopoulos himself explains it:

“[T]his study—like every study of IRV’s record in real-world elections—is necessarily limited to the candidates on the general election ballot. Among these

candidates, IRV is nearly certain to elect the Condorcet winner. It could be, however, that voters would have favored another candidate over the observed Condorcet winner, had this other candidate been on the general election ballot. It could also be that this other candidate would have lost to the observed Condorcet winner, in which case IRV would have failed to elect the “true” Condorcet winner. Some scholars argue that there are many such “missing moderate[s]”: centrist candidates who would have been Condorcet winners, had they been on the general election ballot, who would have been defeated under IRV, and who don’t appear in the general election because they either lost in the primary election or didn’t run in the first place. These scholars’ claims are plausible but impossible to test with actual election results.”

Dennis doesn’t mention Stephanopoulos’s acknowledgement of this key point.

Dennis, moreover, seems to dismiss the possibility of this phenomenon as mere conjecture. Knowing that I had previously raised the example of Rob Portman not running for reelection in 2022 even though he almost certainly would have been the Condorcet winner had Ohio used a Condorcet-consistent electoral system (and assuming that Portman then would have run since it wouldn’t have been futile for him to do so, the way it would have been under either the existing plurality-winner system or IRV), Dennis dismisses it a “pure hypothetical.” But this dismissiveness is like the proverbial ostrich with its head in the sand. If one is paying any attention at all to contemporary American politics, one sees myriad examples of rule-of-law Republicans being squeezed out of contention, unable to compete in the current polarized political environment against MAGA Republicans and Democrats, even though in many instances a majority of voters would prefer the rule-of-law Republican candidate to either the MAGA Republican or the Democrat head-to-head. In all of these circumstances, IRV would replicate the existing polarized contestation between the MAGA Republican and the Democrat, whereas the rule-of-law Republican would win a Condorcet-consistent election as the candidate preferred by a majority to either alternative and thus “the real preference of the Voters” (to use James Madison’s term for a Condorcet winner).

To take the most obvious example, which Dennis ignores: last year’s presidential election. If IRV had been used to determine the winner, Donald Trump still would have beaten Kamala Harris. But as I’ve explained elsewhere, Trump’s victory over Harris is a clear case of the “center squeeze” problem. If a Condorcet-consistent electoral system had been in place that enabled a third candidate in between these two to demonstrate majority support against each head-to-head, that third candidate—presumably, a rule-of-law Republican like Nikki Haley (or possibly Larry Hogan)—would have won the election instead of Trump.

Given the enormously consequential difference that Condorcet Voting instead of IRV would have made for last year’s presidential election, it’s simply preposterous to claim as Dennis does that IRV can adequately handle the problem of polarization as a “real-world” matter and there’s no need to consider Condorcet Voting as a potentially better remedy for the problem.

Dennis’s second point is a much more significant one and needs to be taken very seriously. It is based on the well-known truth that all electoral systems are susceptible to strategic manipulation by candidates and their supporters. Their differing mathematical properties incentivize candidates and voters to act in various ways, and some of these incentives and the strategic behavior they induce can perversely undermine the purpose of adopting an electoral system in the first place.

Dennis argues that Condorcet Voting creates incentives for candidates on the left and right to undermine a centrist likely to win under the system, thereby producing the exact opposite of its intended effect and polarizing the electoral process even more by driving candidates and voters to even further extremes. This will occur because candidates on the left and the right will encourage their supporters to “bullet vote,” meaning to express a preference only for their top-choice candidate and refrain from expressing a preference between the two other candidates. (In a Condorcet-consistent system that uses ranked-choice ballots, bullet voting would mean ranking only one’s top-choice candidate. In a Condorcet system with ballots that have their voters express their head-to-head preferences directly, bullet voting would mean abstaining from the direct head-to-head that doesn’t involve one’s most preferred candidate.) As part of this bullet voting strategy, Dennis envisions the “demonization” of the centrist candidate by both the left and the right, making the campaign’s messaging much more toxic. The upshot would be both the electoral defeat of the centrist, contrary to the expectations of how Condorcet Voting should work under conditions of polarization, and the development of a political culture “amplifying” polarization to make it far worse than what previously existed.

By contrast, Dennis contends that IRV counteracts polarization by causing candidates on the left and right to woo the centrist’s supporters in order to earn their second-choice votes. As Dennis correctly observes, there is generally no incentive to bullet vote in an IRV system because the mathematical properties of its sequential elimination procedures mean that a lower-ranked preference cannot harm a higher-ranked preference. This provides a sound reason for candidates on the left and right to refrain from attacking centrist candidates. But Dennis goes further and maintains that IRV will cause centrist candidates to act like a “magnet” pulling the left and right closer to the center. “Center-squeeze scenarios” would disappear, Dennis says, because IRV “would depolarize these conditions out of existence.”

If Dennis’s analysis of the comparative campaign effects of Condorcet Voting and IRV were correct, it would indeed make sense to abandon any attempt to adopt Condorcet Voting and concentrate solely on the enactment of IRV. But I think that it is far from obvious that his analysis is sound; just the opposite: there are compelling reasons to think that it is not. In any event, it is far too premature to dismiss Condorcet Voting as inevitably counterproductive or to conclude that IRV must always be the better remedy for what ails America’s democracy.

To see why we should not jump to Dennis’s conclusions, let’s start with his prediction about the necessarily depolarizing effect of IRV. Let’s specifically examine it in the context of last year’s presidential election. To do so, let’s suppose that IRV had been in place to determine the winner based on the national popular vote (with a tabulation of ranked-choice ballots given to all voters nationwide) and that, along with Donald Trump and Kamala Harris, Nikki Haley had been on the November ballot as the third most popular candidate who ran for president last year (with popularity defined for this purpose as number of voters for whom the candidate is their top choice). Do we really think that IRV would have worked as Dennis describes and brought Trump closer to the center?

That would have been a wildly unrealistic expectation. True, Trump would have wooed Haley’s supporters, but he would have done so by telling them that they’d be much better off supporting him than Harris as their second choice. Trump wouldn’t have gratuitously demonized Haley, but he still would have viciously demonized Harris, Biden, and Democrats generally. His message to Haley’s voters would be that, once she was out of contention as she inevitably would be under the IRV process, they belonged to him, not Harris, if they wanted to live in a country that wasn’t ruined by inflation, immigration, etc. The politics of the campaign would have been just as polarized and polarizing, with Trump ending up with the same victory over Harris after IRV dropped Haley out of contention—would she even have bothered to continue the campaign all the way through to the end, knowing she’d be quickly eliminated in the IRV process?—and, after Trump’s inauguration, we’d be witnessing the same polarized and polarizing consequences of his executive actions as president.

Now let’s consider Dennis’s predication about how Condorcet Voting would actually operate in practice. Yes, Trump would have had a strong incentive to urge his supporters to bullet vote in order to prevent Haley from winning. But there would have been a serious risk of this strategy backfiring and causing the election of Harris. Moreover, Harris would have had a strong incentive to induce this outcome by urging her supporters to vote for Haley over Trump, a message consistent with Harris’s paramount concern about Trump being an existential danger to American democracy.

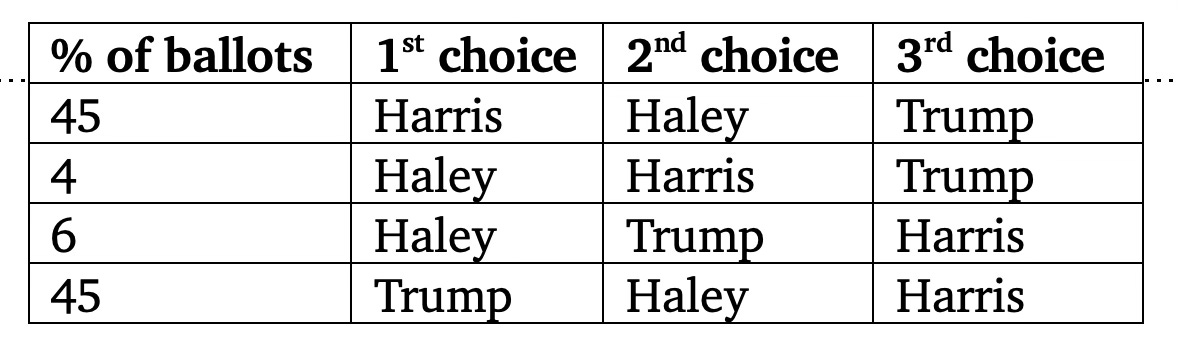

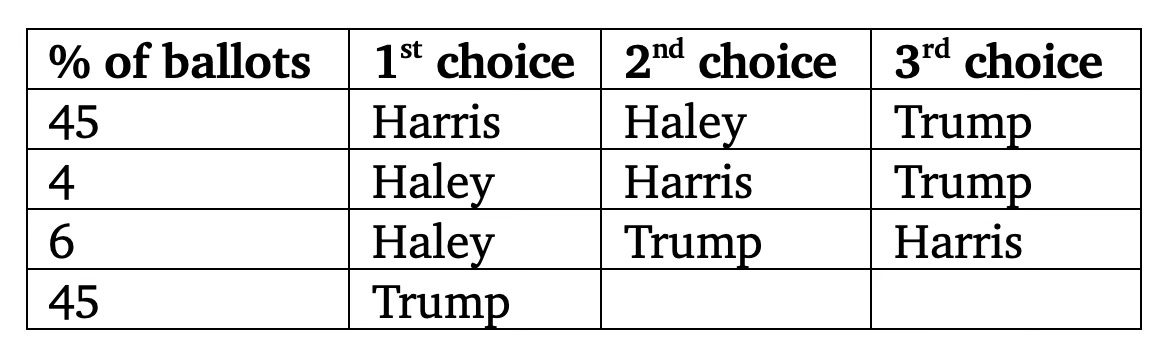

A simplified example will help us see this point. Assume that these would be the ranked-choice ballots cast if all voters were sincere in their preferences:

Now suppose that Trump successfully persuades all of his supporters (that is, the voters who rank him first) to bullet vote, so that these become the ballots:

In this situation, Condorcet Voting would produce one head-to-head victory and one head-to-head defeat for each of the three candidates:

Trump beats Harris: 51-49

Haley beats Trump: 55-45

Harris beats Haley: 45-10 (with 45% of voters abstaining from this head-to-head)

How Condorcet Voting breaks this three-way tie depends on the specific tiebreaker used. The tiebreaker that is most consistent with principles of Madisonian democracy, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, is to elect the candidate whose single head-to-head defeat has the narrowest margin of defeat. (This tiebreaker assures the election of the candidate who has the broadest support within the electorate.) Harris would win the tiebreaker. She has the narrowest margin of defeat: 51-49=2. (Trump has 55-45=10. Haley has 45-10=35.)

Given this, Harris has every incentive to urge all of her voters to be sure to vote for Haley over Trump—as they should, from her perspective, given the dire threat that Trump poses for democracy. But what if Trump, recognizing the possibility that Harris will win if he urges his supporters to bullet vote, abandons that strategy and urges his supporters to vote for Haley over Harris? Or he just stays silent on how his supporters should handle the choice between Haley and Harris? Well, then, there’s the possibility that Haley will end up the Condorcet winner after all. While that’s obviously not as good as a Harris victory from Harris’s own perspective, it’s still a far, far better outcome from her perspective than a Trump victory, given that Haley in no way poses the same existential threat to democracy that Trump does. Remember, Harris is campaigning with Liz Cheney and other “never-Trump” Republicans on the paramount need to defeat Trump.

Thus, in the context of the 2024 presidential election, Condorcet Voting most likely would have produced either a Haley or Harris victory, with which of these two outcomes depending on the extent Trump’s voters acted sincerely or attempted an ultimately counterproductive manipulative strategy. Either outcome is vastly preferable from the point of view of seeking depolarization of American politics than Trump’s victory. Yet a Trump win is what IRV would have produced, just the same as what happened under the existing electoral system.

Based on what Dennis wrote in his piece, we can anticipate him responding to this discussion of last year’s presidential election by asserting that it’s an “isolated” or “rare” aberration of IRV’s general superiority to Condorcet in coping with polarization. But I don’t think we can be so confident of that. The MAGA movement is not just Trump, even though he currently is its obvious and powerful leader. American politics today and for the foreseeable future has three main factions: (1) the newly dominant MAGA or authoritarian populist wing of the Republican party, (2) the now-eclipsed traditional rule-of-law wing of the Republican party, and (3) the Democrats. The question the nation confronts is how the its electoral institutions will handle the competition among these three factions in their efforts to gain power in government.

There is good reason to believe that if IRV were adopted in every state, the MAGA movement would continue to dominate in virtually every “red” state where Republicans currently crush Democrats in November. The MAGA movement is characterized by its hardline positions on immigration and other cultural issues, including its embrace of election denialism and glorification of the J6 insurrectionists. There is no reason to expect that MAGA candidates would moderate their positions just because IRV rather than plurality-winner electoral systems were in place. Instead, MAGA candidates would simply force the supporters of rule-of-law GOP candidates to choose between them and the Democrats, knowing that enough of these voters would make this choice in their favor. In states like Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Tennessee, and others, the MAGA candidate will steamroll the rule-of-law GOP candidate on their way to trouncing the Democrat, and this is true whether the electoral system is the existing one—where the steamrolling occurs in the Republican primary before the trouncing in the general election—or under IRV, where the steamrolling occurs in IRV’s elimination process before the trouncing in IRV’s final round.

Contrast this with what would be reasonable to expect if Condorcet Voting were used in these red states. MAGA Republicans immediately would be threatened by the high likelihood that rule-of-law Republicans would win instead of them. MAGA Republicans surely would contemplate telling their supporters to bullet vote in an effort to thwart these rule-of-law Republican victories. Crucial would be what Democrats in these states would then do. If they too engaged in bullet voting, as Dennis would predict, they would only assure the election of MAGA candidates. But if Democrats all voted for rule-of-law Republicans over MAGA candidates on their Condorcet ballots, then they potentially could avoid the election of MAGA candidates with one of two outcomes: either the rule-of-law Republican would be the Condorcet winner or their own candidate would win the Condorcet tiebreaker (just as Harris would in the previous presidential example). While Democrats obviously would prefer their own candidate to win instead of the rule-of-law Republican, either of those two outcomes would be much better, in their view, than a MAGA victory.

Thus, Democrats in these red states should pursue as energetically as possible the adoption of Condorcet voting, which would not only give them a chance of actually winning statewide elections that they otherwise wouldn’t, but would make much more likely at least a result that they would prefer to the virtually foregone conclusion of unremitting MAGA victories. If conversely Democrats managed to get IRV adopted in these red states (an unlikely prospect, to be sure), they would be no better off than they currently are. They still would be doomed to MAGA victory after MAGA victory, with no end in sight.

How can Democrats possibly get Condorcet voting adopted in these red states, especially when MAGA Republicans would be vehemently opposed based on their obvious self-interest? The only way would be for Democrats to forge a reform coalition with the remaining rule-of-law Republicans in those red states before they become entirely extinct. It would be in the self-interest of these rule-of-law Republicans, as well as the self-interest of Democrats, to enter this partnership for Condorcet-based electoral reform. It would give both these rule-of-law Republicans and Democrats a chance to win statewide elections that neither otherwise would have under either the existing plurality-winner system or IRV. As long as the combination of rule-of-law Republicans and Democrats makes up a majority of voters—which it still does in many red states despite the increasing electoral strength of the MAGA movement—there is a chance of getting Condorcet voting adopted in these states despite the inevitable MAGA opposition.

Dennis asserts that if Condorcet voting were adopted anywhere, it would be unstable and short-lived, and political parties on the left and right would “gang up on the Condorcet system itself and repeal it altogether.” But if Condorcet voting were adopted by a partnership of rule-of-law Republicans and Democrats in the way that I’ve suggested, it should remain immune from this type of repeal. It would be self-defeating for Democrats to combine with MAGA Republicans to undo the reform that’s the only way for Democrats to have a chance to win in these red states.

If the coalition of rule-of-law Republicans and Democrats kept Condorcet voting in place over an extended period of time, the likely long-term consequence would be to moderate the MAGA movement. In order to win elections, its candidates would need to become much more like the rule-of-law Republicans, to the point where Democrats would be indifferent between the two types of GOP candidates. MAGA candidates, in other words, would need to dispense with election denialism and other authoritarian tendencies. That consequence would be the best possible outcome from the perspective of eliminating the evils of partisan polarization and protecting the ongoing operation of democracy.

In sum, it would be extremely unwise to dismiss consideration of Condorcet voting as a potentially valuable electoral reform and to rest exclusively on IRV as the only sensible way to conduct statewide elections. (Elections for legislative districts, which could be reformed by proportional representation, is an entirely separate topic.) Condorcet voting need not be adopted everywhere. IRV might work perfectly fine in some states, especially “blue” ones (like Massachusetts, where Dennis is from) that face little threat from MAGA-type authoritarian extremism under any electoral system. But Condorcet voting should not be banished from the election reformer’s medicine cabinet. It may prove necessary to prescribe Condorcet voting as the only way to make democracy healthy again for some types of elections in some places.

(Note: this essay has been updated to correct an arithmetical error.)

I understand how someone can promote IRV when they're not aware of center squeeze, but I cannot understand why they would be so stubbornly persistent in promoting IRV even after understanding its biggest flaws.

The FairVote crowd have really lost the plot, and are just harming their own cause at this point, continually pushing a broken voting system that doesn't actually fix the things they claim to want to fix, and that's getting banned in more places than it gets adopted.

We need to remember that, in order to value our votes equally, that Single-Winner, Multi-Winner, and Apportionment of Delegates (Presidential primary) are very different problems.

1. Single-Winner: There is no proportionality to be had with a single winner. It's winner-take-all. So then, the *only* way to value our votes equally is Majority Rule. And Condorcet RCV respects Majority Rule in elections where Hare RCV does not. Condorcet is clearly better at respecting Majority Rule and the equality of our votes.

2. Multi-Winner: Now proportionality comes into the equation and then something like the Weighted-Inclusive Gregory Method (PR STV) might be the method that best reflects apportioning multiple seats in a single legislative district. This, of course, has quota, surplus votes that get transferred, and *then* a Hare-ish elimination of candidates.

3. Apportionment of state delegates to the DNC or RNC: This is a solved mathematical problem and it's used to apportion 435 U.S. House Representatives to the 50 states. Same math, and that method should be used to apportion a known number of delegates to candidates, based on the number of votes that each candidate gets.