Self-Districting Solves the Problem of the Supreme Court’s South Carolina Case

If voters are permitted to choose the legislative districts they are in, then there is no need for courts to grapple with the thorny problem of how states handle the role of race in districting.

One of the most vexing areas of election law is the role of race in legislative districting. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), especially as amended in 1982, requires mapmakers who redraw legislative districts every decade (to adjust for population changes) to avoid diluting the electoral power of minority voters. Determining when a new map causes unlawful vote dilution has proved challenging for courts, as evidenced by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision last year in Allen v. Milligan.

Added to the difficulty of determining when a new map violates the VRA, the Court’s interpretation of the Equal Protection guarantee in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution has made it unconstitutional for legislative mapmakers to give too much consideration of race when drawing district lines. The combination of the VRA’s prohibition against racial vote dilution and the Constitution’s prohibition against excessive race-based redistricting has left mapmakers caught between the proverbial “rock and a hard place”—or like Odysseus trying to navigate between Scylla and Charybdis, if you prefer that reference. Feeling “damned if you do and damned if you don’t,” mapmakers (and judges) have struggled to find a Goldilocks-like “just right” position between unacceptably too much and too little.

Now, the Supreme Court has divided sharply again over one of these cases. In Alexander v. NAACP, the justices split along the regrettably routine 6-3 partisan lines (Republican appointees in the majority, Democrats in dissent) over the map that South Carolina’s legislature adopted for the state’s congressional districts after the 2020 census. The NAACP argued that race unconstitutionally motivated the map’s district lines. The state defended its map on the ground that the Republican-dominated legislature was motivated by partisanship, not race, in drawing the lines that it did. It wanted to engage in a partisan gerrymander, in order to increase the number of congressional seats from South Carolina that Republicans would win. The fact that the new districts looked like the result of race-based line-drawing was, according to the state, the incidental byproduct of the legislature’s partisan objective resulting from the large overlap between Blacks and Democrats in South Carolina.

A reader would be forgiven for thinking that confessing to having engaged in partisan gerrymandering ought not to be a valid defense. But in fact, in an earlier case, Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Supreme Court decided that the Constitution gives federal judges no power to constrain partisan gerrymanders. Consequently, in the new South Carolina case, Alexander v. NAACP, the six-member majority of the Court ruled that as long as a map can be explained as a partisan gerrymander, and there’s no clear proof that race rather than partisanship was the motivation for the map, then it cannot be condemned as unconstitutionally race-based.

My point here is not to evaluate whether the Court’s ruling in Alexander was right or wrong. Others have already done so, and I’m inclined to agree with Nick Stephanopoulos that the root problem is the Court’s earlier Rucho decision. Mapmakers should not be permitted to be blatantly and excessively partisan in drawing district lines. But as long as Rucho remains the law, I’m not so sure it’s wrong to say that any map that can be fully explained as partisan should not voided for being race-based (at least not without some sort of “smoking gun” that proves the mapmaker’s improper racial motivation).

Instead, the point I want to make—and to stress as emphatically as I can—is that this messy problem of the relationship of race to redistricting can, and should, be avoided by adopting a new approach to the task of legislative districting.

I call this new approach self-districting because its essential feature is that the voters themselves, and not the government, choose the constituency to which voters belong. In other words, the voters themselves decide whether or not they want to be put into a legislative district based on race—or whether they would prefer to be districted on the basis of some other attribute or criterion. Because the voters and not the government would be making these decisions, there would be no constitutional issue regarding racial discrimination by the government in violation of Equal Protection for courts to address. And because voters would be empowered to ensure that districts are not drawn to dilute their fair share of control over the election of legislative representatives, there would be no issue of vote dilution to arise under the VRA.

Here’s how a self-districting system would work (a more detailed description can be found in this Kentucky Law Journal article):

It would be a two-stage process. In the first stage, various groups wishing voters to join them would register with the state’s election administration agency (usually the secretary of state’s office). This agency would operate a website listing and describing all the registered groups. Voters would have the opportunity to join whichever group they wished by a specified deadline.

After the deadline, the agency would determine how many voters joined each group. The number of legislative districts a group would be entitled to form would depend on the number of voters in the group. Based on the constitutional principle of one-person-one-vote, the agency would establish the number of voters in each district. For example, if a state had 10 congressional districts and 5 million voters, each district would have 500,000 voters. Thus, a group would need to have 500,000 voters join it to be eligible for one district.

If during this first stage, a group attracted 1 million voters, it would be entitled to two districts—and 3 districts if it attracted 1.5 million (and so forth). To make all districts have the same number of voters, the election agency would administer two adjustments. First, if a group failed to attract even 500,000 voters, it would get no district, and all its voters would be assigned to an unaffiliated district. Second, if a group attracted more than 500,000 voters but fewer than 1 million, the number of voters it attracted above 500,000 would be randomly withdrawn from the group’s district and reassigned to the unaffiliated district (and this same principle would apply to any fraction of the group’s total members that fell between multiples of 500,000).

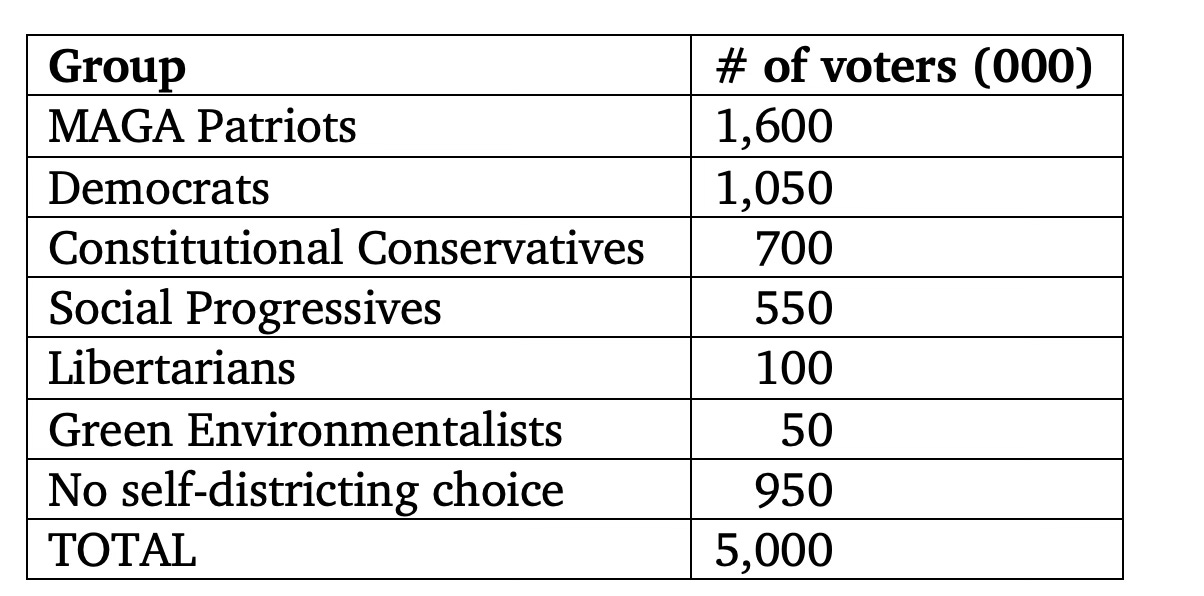

To illustrate this process, let’s imagine that in our state of 5 million voters and 10 congressional districts, the voters joined these groups in these numbers:

These groups, one will immediately notice, look a lot like political parties. That’s because I would expect that, if this self-districting system were implemented, political parties would be effective in persuading voters that they would have the most electoral clout if they joined groups as large as possible, to command as many districts as possible, rather than fragmenting in a myriad of separate interest groups. Even so, voters would be able to join any group that registered with the electoral agency, whether that group organized itself based on race, age, occupation, geography, or any other characteristic.

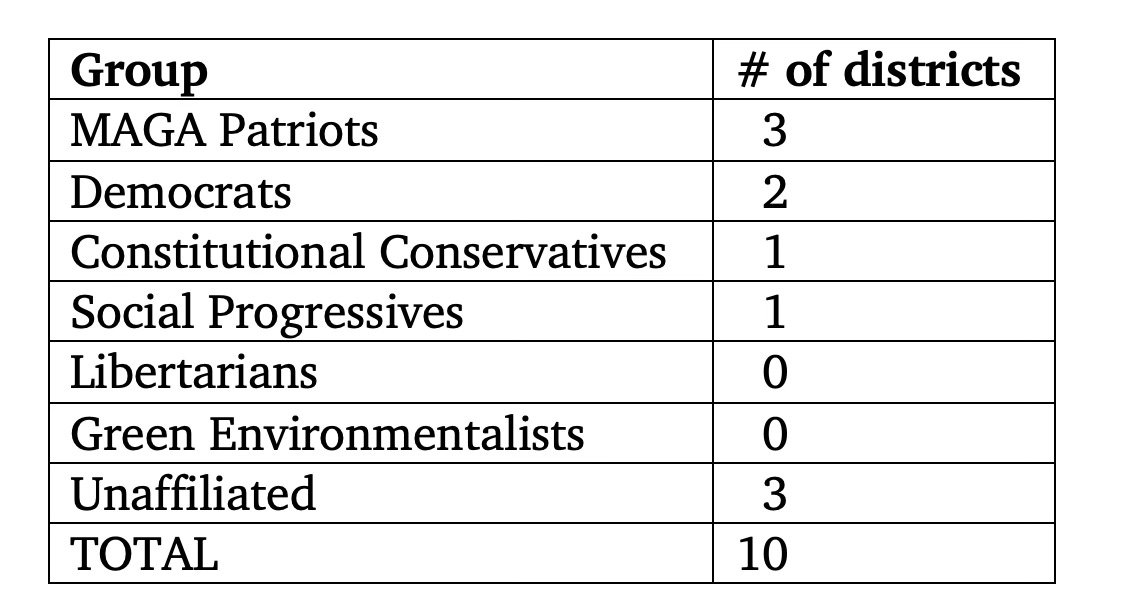

Given these numbers of voters in each group, the agency would assign each group the following number of districts:

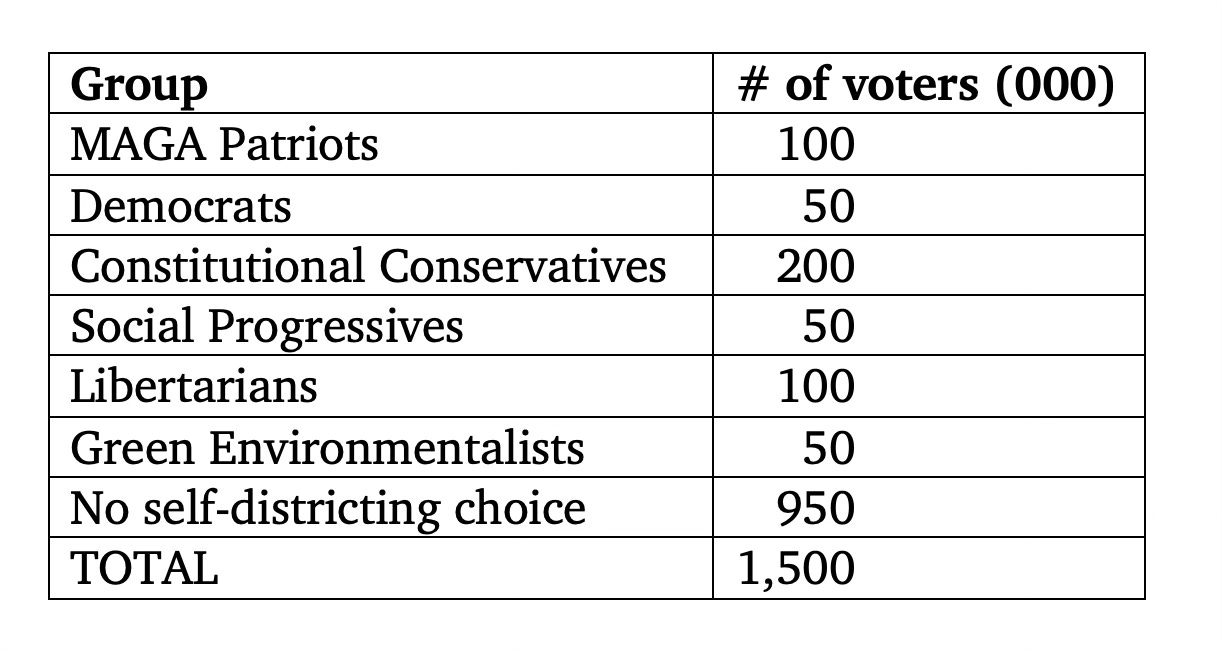

To make the number of voters in each district equal, the following number of voters from each group would be randomly assigned to one of the three unaffiliated districts:

For any group that has more than one district—like the MAGA Patriots, Democrats, and Unaffiliated—the group would be subdivided into its allocated number of districts by a computer program strictly on the basis of geography. There would be no partisan gerrymandering, because the choice of how many districts each party controlled would be made entirely by individual voters when joining groups in the first stage of this self-districting process. Democrats, for example, would control two (and only two) districts, no matter how the 1 million voters in its two districts were subdivided geographically.

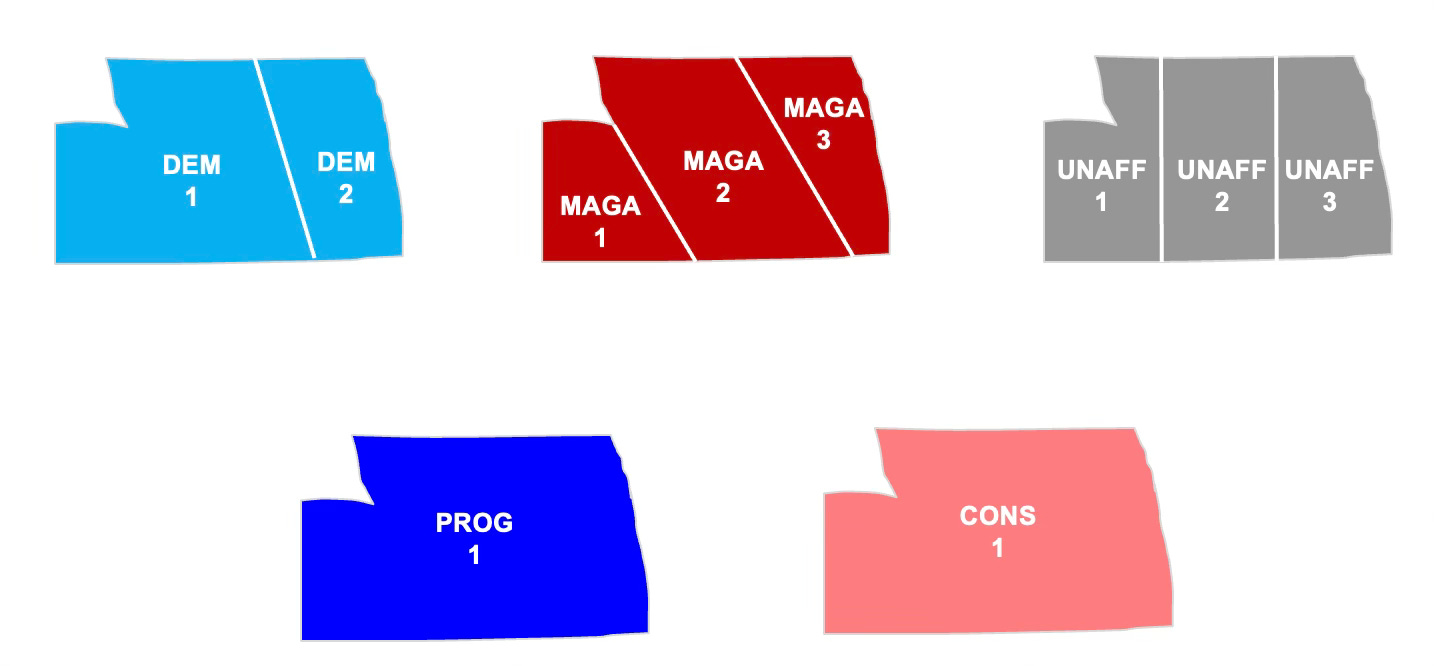

The consequence of this districting procedure would be overlapping districts. Groups with only one district would have a single statewide district, much like Wyoming, Alaska, and other low-population states have now. But in our hypothetical state with ten congressional districts, on top of the single statewide district that the Constitutional Conservatives and Social Progressives each would have, there would be another map subdividing the state geographically into two districts for the Democrats. There would also be another map subdividing the state geographically into three districts for the MAGA Patriots—and yet another map subdividing the state geographically into three other Unaffiliated districts.

These districting maps for this hypothetical state could look something like this:

After all districts are set according to this procedure, the election would proceed to stage two. In this second stage, candidates seeking to represent a district would gather signatures to get on the ballot. Voters would cast these ballots in the November general election, just as they currently do. For conducting this election, I would favor a form of ranked choice voting consistent with the principles previously discussed in Common Ground Democracy—in other words, a method of tabulating the ranked-choice ballots that assures the election of a candidate who is preferred by a majority of voters compared to each other candidate on the ballot. But any form of ranked-choice voting could be employed for the second stage of this system.

For those group-specific districts formed on the basis of the self-districting decisions made by voters in the first stage of the process, the second-stage election in November looks more like a partisan primary than a November general election in the current system. To return to our hypothetical example, in either of the two districts formed by Democrats, all the candidates will themselves also be Democrats, just as in a current partisan primary. But unlike the problem of partisan primaries in the current system, where the choice made by the primary voters may eliminate the candidate most preferred by the district’s median voter, the November election in the self-districting system can be structured so that the candidate preferred by the district’s median voter will win. And because voters in these group-specific districts will have chosen to be in a district with fellow members of the group, these voters will not feel the powerlessness currently felt by Democrats in uncompetitive Republican districts—and vice versa.

To be sure, voters assigned to an Unaffiliated district will experience a second-stage November election similar to November general elections in the current system. Because there will be voters from different parties and other groups in an Unaffiliated district, candidates from different parties (and perhaps also independent candidates) will be on the November ballot in an Unaffiliated district. But a form of ranked choice voting consistent with Common Ground Democracy principles can also be used for the November election in an Unaffiliated district—just as it can be used for November elections to fill legislative seats that have been districted by the government according to current redistricting practices.

Using a Common Ground Democracy form of ranked choice voting for the November elections in both the group-specific and Unaffiliated districts would be the way to make a self-districting system most consistent with Common Ground Democracy principles. If self-districting is employed in a state that is highly polarized on the basis of partisanship, each polarized party will control a share of the state’s districts roughly proportional to the party’s share of the state’s whole electorate. But at least the representative elected in each of the polarized party’s districts will correspond to the party’s median voter. Also, the representative elected in each Unaffiliated district will tend to reflect the position of the whole electorate’s median voter. Moreover, as long as no single party will control a majority of districts in this self-districting system—as almost certainly will be true in a highly polarized state—the representatives elected from Unaffiliated districts will hold the balance of power in the legislature. Any party seeking to control a majority of seats in the legislature will need to form a coalition that includes representatives from Unaffiliated districts. This fact will tend to cause the creation of legislative coalitions willing to engage in the kind of compromises necessary to enact policies in the public interest, which the principles of Common Ground Democracy aim to foster.

But however much self-districting may be consistent with the principles of Common Ground Democracy, and whatever its other merits may be, one thing is clear: self-districting avoids the problem of policing the inappropriate consideration of race in the context of redistricting—a problem made manifestly apparent once again by the Supreme Court’s bitterly divided opinions in the South Carolina case, Alexander v. NAACP.

Let the voters choose their own districts, and the issue of whether the government gave too much (or too little) consideration of race in drawing districts simply disappears.

Self-districting with more representatives elected by an uncensored ballot would restore accountability to voters.

There’s no need to reinvent or simulate open-list proportional representation. It already has a track record of success - has the bugs worked out - and accomplishes what is proposed here.