Bracket Voting

Elections Should Be Structured Like Familiar Sports Tournaments

March Madness is upon us, making this an opportune time to propose a new form of voting that resembles the format of the NCAA’s immensely popular tournaments for men’s and women’s basketball.

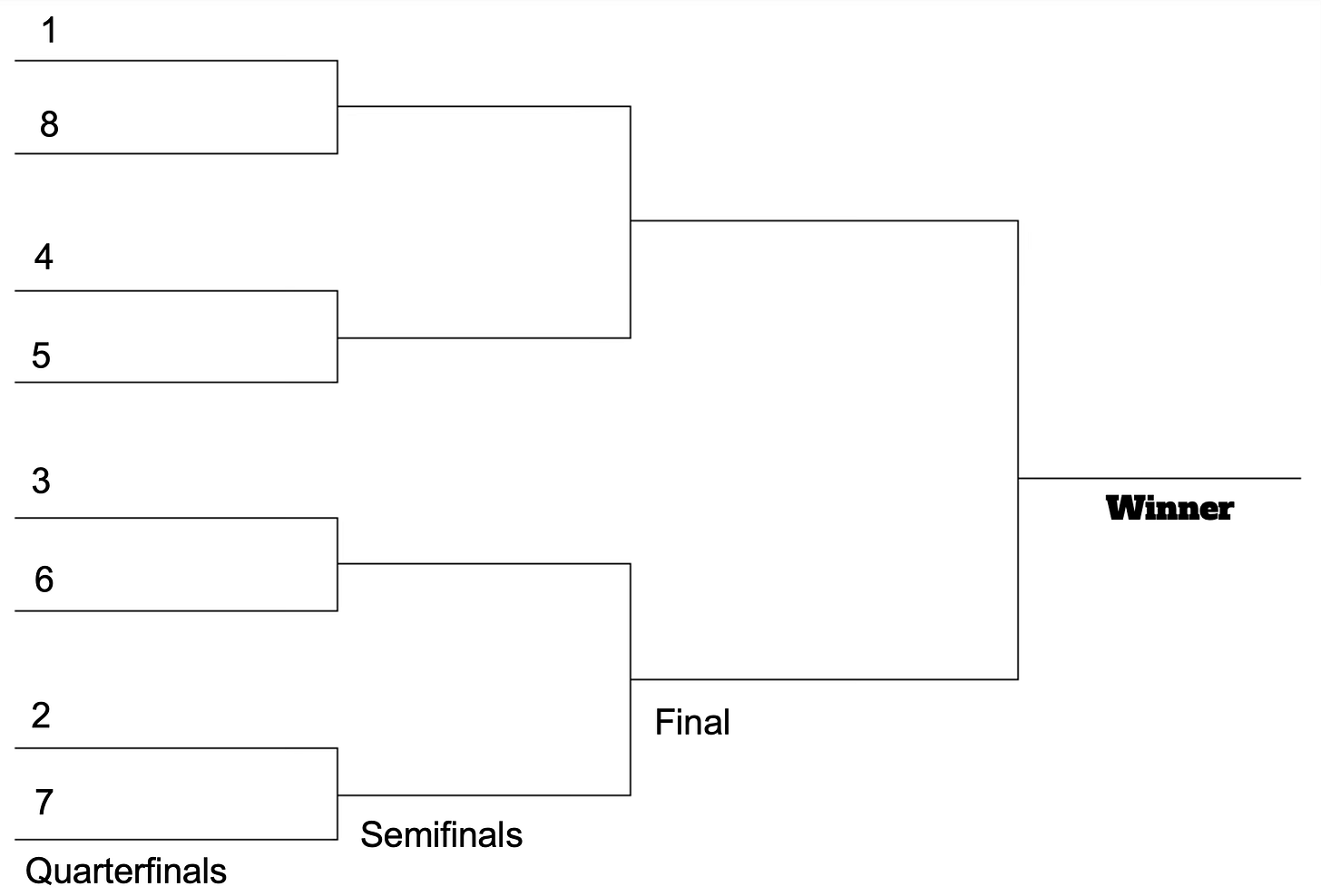

I call it “Bracket Voting” because it has the same bracket structure as March Madness—and many other sports tournaments, like college football’s new playoff format. In a bracket tournament, competitors face off in pairs for each round, with the winner advancing to the next round of the tournament while the loser is eliminated.

The number of rounds depends upon the number of competitors. With eight teams, for example, there are three rounds: four quarterfinal matches, followed by two semifinals, and one final that determines the tournament’s overall winner.

If the number of teams is not a power of two (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, etc.), there need to be “byes” in which some teams do not need to compete in a preliminary round. In the new college football playoffs, for example, there are twelve teams, so the four highest-ranked teams get byes for the first round, while the other eight teams play four head-to-head games to reduce the total number of teams to eight for the quarterfinals.

A bracket tournament differs from a round-robin tournament, in which each competitor has a head-to-head match against every other competitor and the competitor with the most head-to-head victories wins the tournament. A bracket tournament is more efficient than a round-robin tournament because a bracket tournament needs far fewer matches to determine the winner than a round-robin tournament. With eight teams, a bracket tournament requires seven matches: four quarterfinals, two semifinals, and one final. A round-robin tournament with eight teams requires 28 matches! (The formula for determining the number of matches necessary for a round-robin tournament is n(n-1)/2, where n is the number of competitors.)

A round-robin tournament can end in a tie when the largest number of head-to-head victories is shared by more than one competitor. Consequently, all round-robin tournaments require some form of tiebreaker rule, a point that is especially relevant in the electoral context. A bracket tournament requires no tiebreaker, as the winner of the final match wins the whole tournament. (Some sort of tiebreaker rule might be needed to settle which competitor wins a particular match, as in the case of penalty kicks to settle a soccer match that ends in a tie, but that is a separate matter from the entire tournament needing a tiebreaker because more than one competitor has won the most matches. A round-robin soccer tournament, for example, requires both kinds of tiebreakers, while a bracket soccer tournament requires only the match-specific and not whole-tournament tiebreaker.)

Because a bracket tournament does not involve each competitor facing off against each other competitor, it matters greatly which competitors have a match against which other competitors. Accordingly, bracket tournaments have seedings that rank each competitor from top to bottom, with the top-seeded competitor facing the bottom-seed in the first round. Thus, in an eight-team bracket tournament, the quarterfinals will have the first seed face the eighth seed, the second seed face the seventh seed, the third seed face the sixth seed, and the fourth seed face the fifth seed.

Some bracket tournaments employ random seeding. In this situation, past performance is irrelevant to the determination of which opponents each competitor faces. Instead, the luck of the draw potentially will be a factor in determining the outcome because, unlike in a round-robin tournament, there won’t be an opportunity for each competitor to face every opponent.

Bracket Voting Has the Same Basic Structure as Any Bracket Tournament

Bracket Voting follows the same format. Each pair of candidates in the election has a head-to-head match, with the winner advancing to the next round and the loser eliminated.

Bracket Voting can be used with any number of candidates in the election. If the number of candidates is not a power of two, there can be byes—as in any bracket tournament. An election with twelve candidates, for example, would have a structure just like college football’s new playoffs. Eight candidates would compete in a preliminary round, with the four winners joined by four other candidates (the ones with byes) for the quarterfinals, and the rest of the electoral process proceeding from there with additional semifinal and final rounds.

In theory, each round of a Bracket Voting election could be conducted on separate days several weeks apart. Imagine the quarterfinals in September, the semifinals in October, and the finals in November. But in the United States, the current expectation is that voters cast a ballot only twice in each electoral cycle—once in a primary, and then again in the general election—and so voters might view it as too demanding to cast three or more separate ballots in a single Bracket Voting election.

It is possible, however, to have Instant Bracket Voting, in which voters cast a single ballot that contains enough information for computers to tabulate all the rounds of the Bracket Voting election. For example, suppose the election has eight candidates. Based on the ballots cast, the computers would tabulate the results of the four quarterfinal matches, then tabulate the results of the two semifinal matches, and then the results of the one final match.

The ballot in an Instant Bracket Voting election could look the same as ballots in any Ranked Choice Voting election. The voters would rank the candidates in order of preference, and then the computers could construct bracket tournament among the candidates based on those rankings. The winner of each match in the tournament would be determined by identifying for each pair of candidates which of the two is ranked higher on each ballot. Of course, the computer would need to know the seedings of the candidates in order to construct the bracket tournament. This would be easy enough to do, as one obvious basis for the seeding would be the number of first-choice rankings each candidate received: the candidate with the most first-choice votes would be seeded first, the candidate with the next most first-choice votes would be seeded second, and so forth.

It would also be possible to make the ballot look like a bracket, just like in an NCAA tournament. The voters would fill out their brackets, just as they do in March Madness (in this case indicating which candidate they prefer to win, rather than which team they predict to win). With this form of the ballot, the seedings of candidates couldn’t be based on information contained on the ballots themselves. But it would be possible to base the seeding on other information—for example, the number of signatures each candidate gathered in order to earn a spot on the ballot. The candidate with the most signatures would be seeded first, and so forth.

In the specific proposal I would most recommend states to consider, Instant Bracket Voting would be used in an election with four candidates (rather than the theoretically feasible eight-candidate example already described). Thus, it would resemble NCAA’s “Final Four” at the end of the March Madness tournament rather than the whole of March Madness, which has 68 teams for both the men’s and the women’s tournaments.

The term “Final Four Voting” is sometimes used to describe something different from the kind of electoral bracket tournament I have in mind. Instead, “Final Four Voting” is a label attached to the kind of electoral system that Alaska currently uses. Alaska has a two-stage electoral system. The first stage is a nonpartisan primary in which all candidates regardless of party affiliation compete against each other. Voters cast a single vote in this nonpartisan primary for the candidate they most prefer. The four candidates receiving the most votes advance to the second stage, in which voters cast a ranked-choice ballot, but these ballots are not tabulated according to the Instant Bracket Voting method I have described. Instead, Alaska’s “final four” ballots are tabulated according to the Instant Runoff Voting method, which eliminates the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes, then redistributes the ballots that ranked the eliminated candidate first to whichever other candidate is ranked second on the ballots. This instant runoff procedure of eliminating a candidate and then redistributing the ballots continues until one candidate has accumulated a majority of ballots (or only one candidate remains).

If instead the Instant Bracket Voting method were used for Alaska’s “final four” election, two semifinal matches would be constructed based on the rankings of the candidates on the ballots cast. The seedings of the candidates for the semifinals could be based, as earlier indicated, on the number of first-choice rankings each candidate receives. Alternatively, seeding could be based on the number of votes each candidate received in the nonpartisan primary.

The Advantage of Bracket Voting

What difference would it make to use Instant Bracket Voting rather than Instant Runoff Voting in an Alaska-style “final four” election following a nonpartisan primary? It could make an enormous difference.

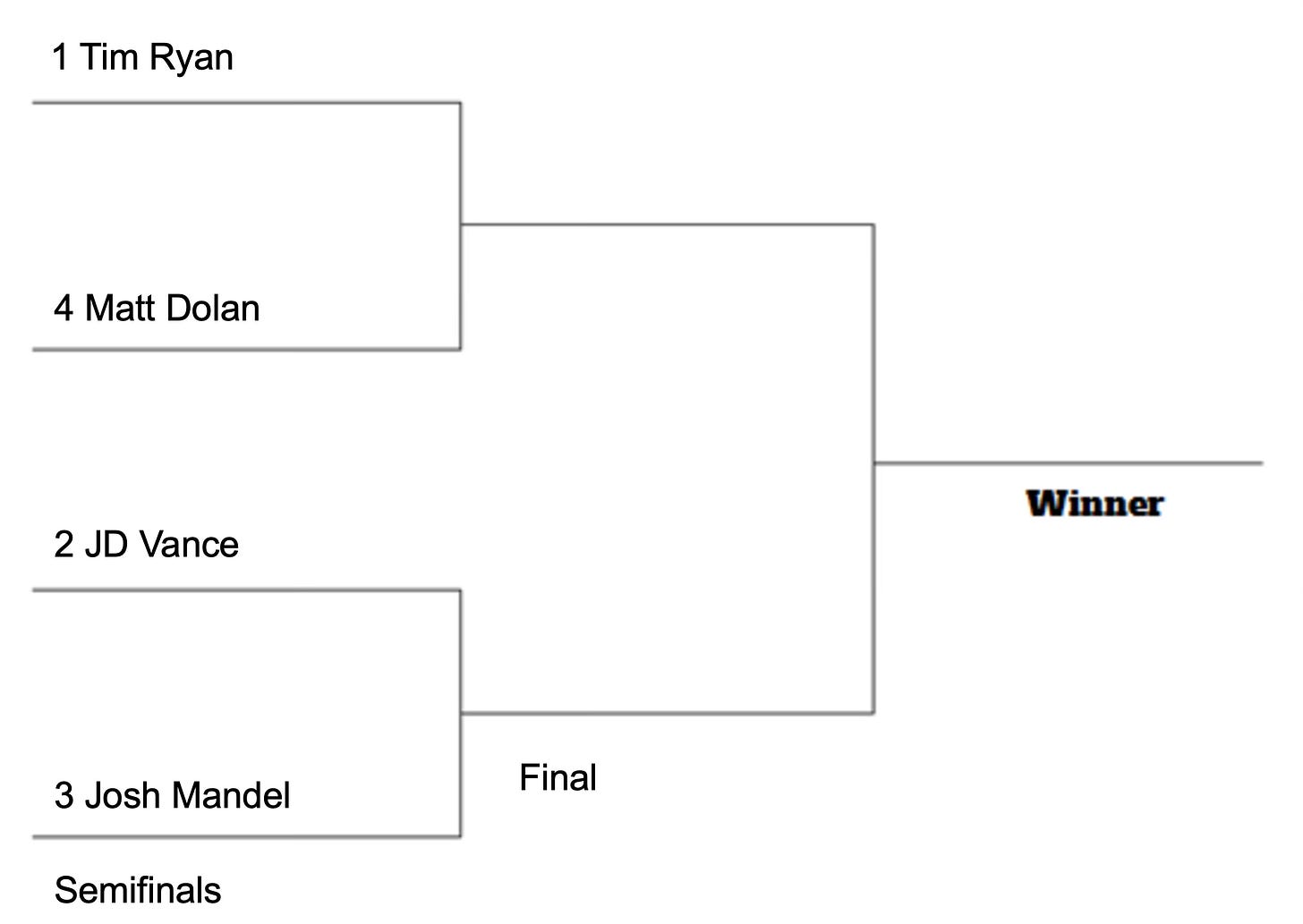

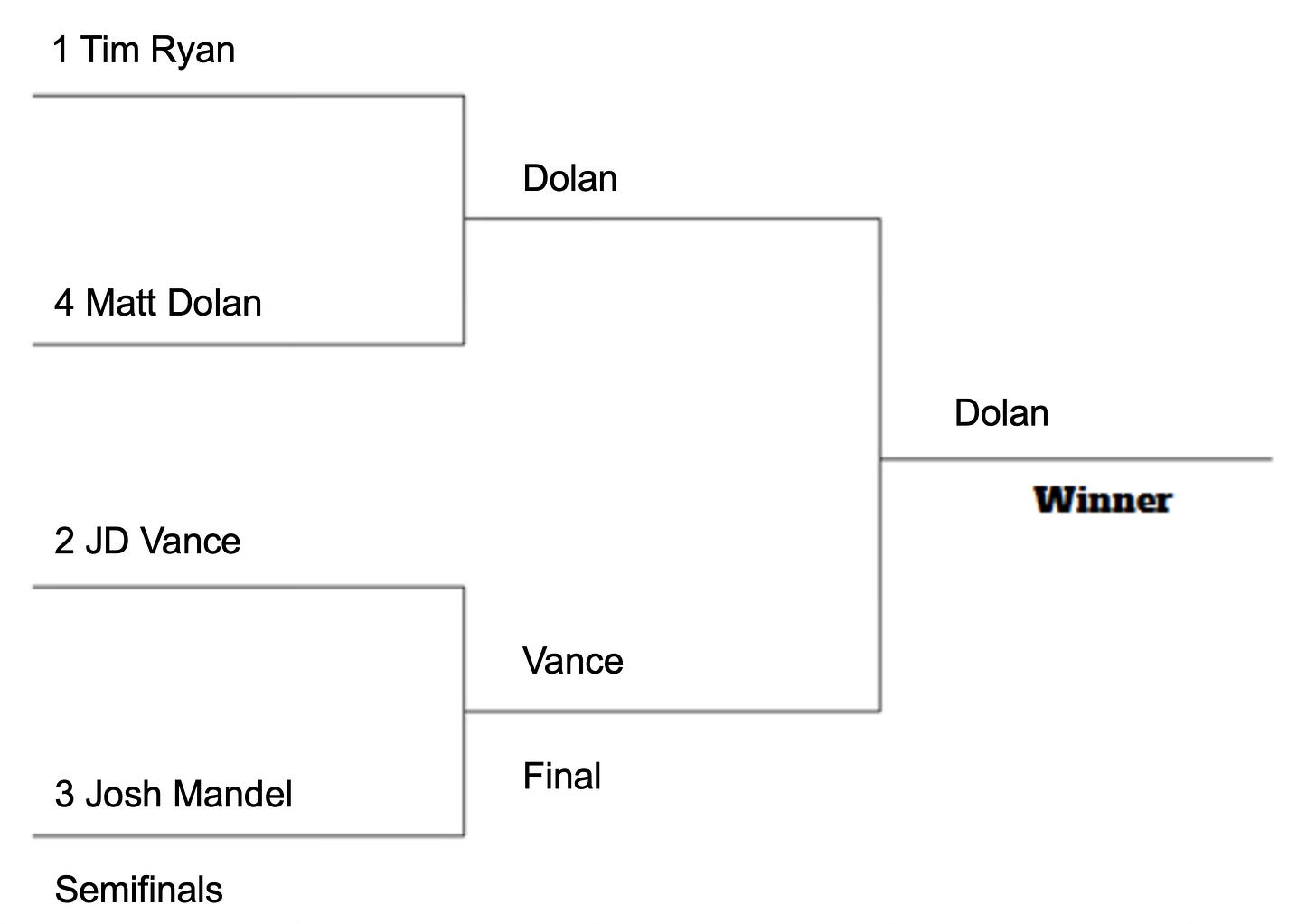

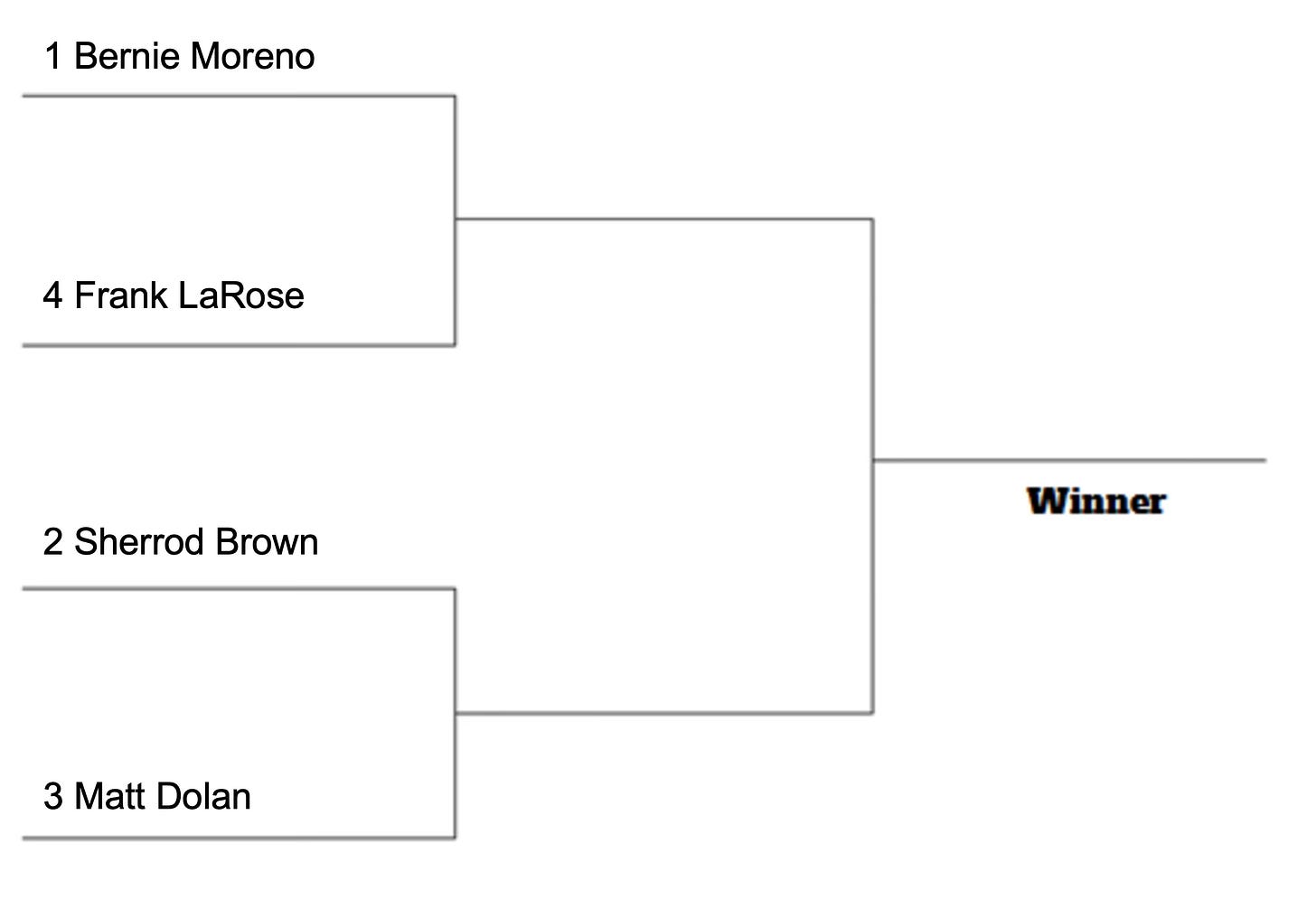

To illustrate, let’s examine Ohio’s last two U.S. Senate elections. Ohio uses traditional partisan primaries, rather than Alaska’s nonpartisan primary. But for both 2022 and 2024 it is possible to identify the four candidates who received the most votes in the Democratic and Republican primaries combined. In both years, the top four candidates can be put into four clearly distinct categories: (1) a Democrat—in 2022, Tim Ryan; in 2024, Sherrod Brown; (2) a Trump-endorsed MAGA Republican—in 2022, JD Vance; in 2024, Bernie Moreno; (3) a MAGA-wannabe Republican who sought, but did not receive, Trump’s endorsement—in 2022, Josh Mandel; in 2024, Frank LaRose; and (4) a traditional non-MAGA Republican in the mold of ex-Senator Rob Portman and Governor Mike DeWine—in both years, Matt Dolan (who was endorsed by Portman and DeWine in the 2024 GOP primary).

If Ohio had used Alaska’s system of Instant Runoff Voting to determine the winner among these four candidates in either year, it is easy to surmise which candidate would have one. The outcome would have been the same as it actually was. The MAGA wannabe and Matt Dolan would have been the first two candidates eliminated in the instant runoff procedure, and the election would have ended up a contest between the Democrat and the Trump-endorsed candidate, with Trump’s candidate winning: Vance in 2022, and Moreno in 2024.

By contrast, if Ohio had used Instant Bracket Voting for an election with these four candidates in 2022 and 2024, there is good reason to believe that Matt Dolan—the non-MAGA traditional Republican—would have won in both years. Assuming that the semifinals in the Instant Bracket Voting election would have been seeded based on the number of votes each candidate received in the primary, the seeding for the semifinals in 2022 would have been:

1) Tim Ryan, Democrat (359,941)

2) JD Vance, Trump-endorsed (344,736)

3) Josh Mandel, MAGA wannabe (255,854)

4) Matt Dolan, traditional GOP (249,239)

In the first semifinal, Dolan, the number four seed, would have beaten Ryan, the number one seed, because Ohio is now a ruby-red state in which any Republican routinely beats any Democrat in a statewide election. This example shows that seeding doesn’t dictate the outcome of a match, just as in March Madness basketball.

In the other semifinal, Vance almost certainly would have beaten Mandel because of Trump’s endorsement. Then, in the final, Dolan most likely would have beaten Vance because Democrats, preferring Dolan to Vance as the less objectionable Republican, would have combined with Dolan’s own supporters plus independents (who also would have preferred Dolan to the much more extreme Vance) to outvote Vance’s ardent pro-Trump MAGA supporters. Trump’s MAGA base is strong in Ohio—as much as forty or perhaps even forty-five percent of the electorate—but not enough to overcome the combination of Democrats, non-MAGA traditional Republicans, and independents.

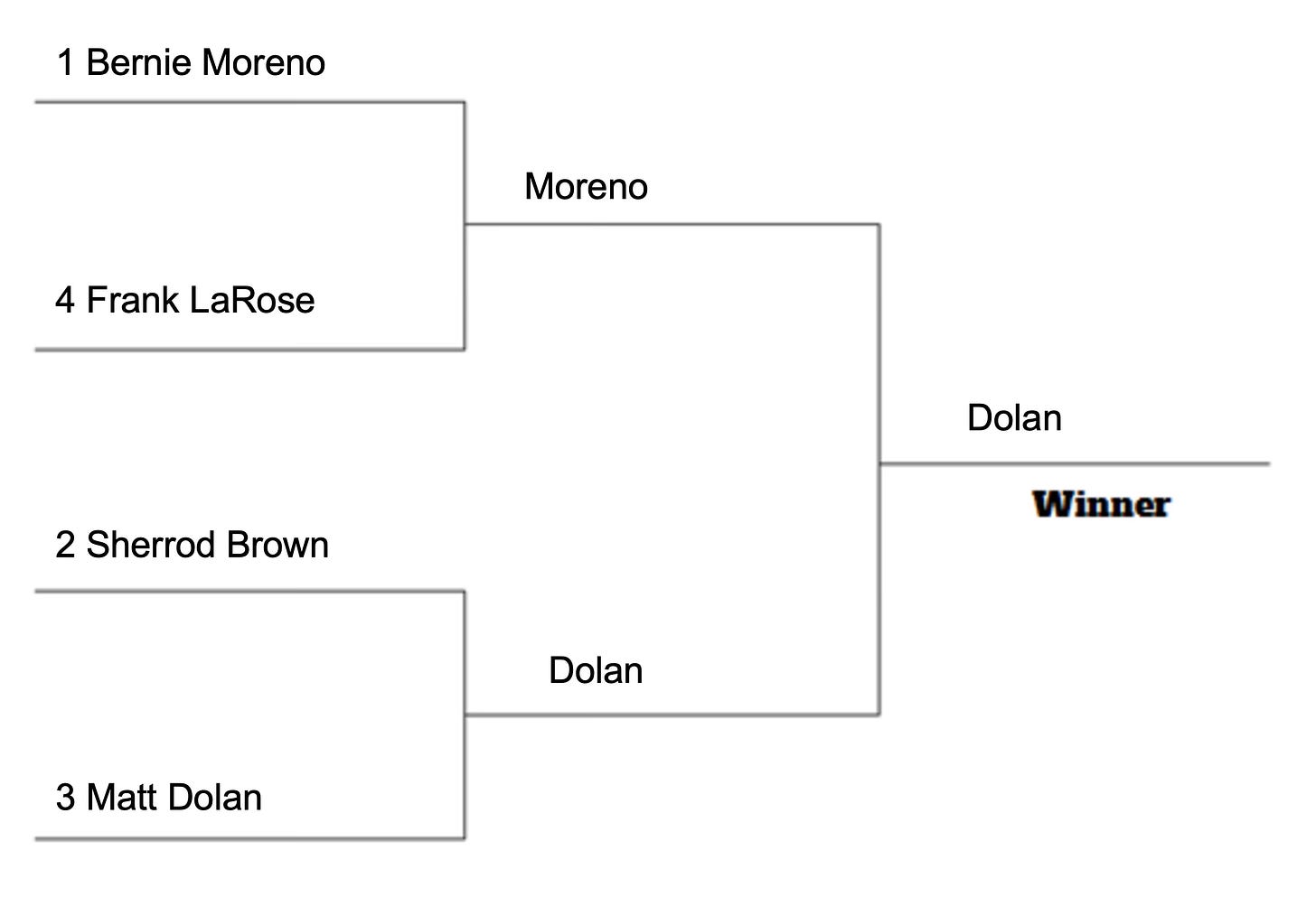

In 2024, the seeding based on votes in the primary would have been a bit different:

1) Bernie Moreno, Trump-endorsed (557,626)

2) Sherrod Brown, Democrat (535,305)

3) Matt Dolan, traditional GOP (363,013)

4) Frank LaRose, MAGA wannabe (184,111)

In the first semifinal, Moreno almost certainly would have beaten LaRose on the strength of Trump’s endorsement. In the other semifinal, Dolan would have beaten Brown for the same reason he would have beaten Ryan two years earlier: because Ohio has become a solidly Republican-dominated state, with virtually any Republican being able to beat any Democrat in a statewide race. In the final, Dolan then would have beaten Moreno because Democrats and independents would have preferred more moderate Dolan over his more extreme Trump-endorsed opponent (just as they would have preferred Dolan to Vance in 2022).

Thus, in both 2022 and 2024 Dolan would have won the Instant Bracket Voting election regardless of what number he was seeded. Using the technical terminology of academic writings on voting systems, Dolan would have been a “Condorcet winner” in either year, meaning he was a candidate capable of beating any opponent head-to-head. The term comes from the French mathematician, Marquis de Condorcet, who explained that in an election involving more than two candidates the one most deserving to win is the one whom a majority of voters prefer to each opponent head-to-head. Instant Bracket Voting is thus a “Condorcet-consistent” electoral method (to employ another technical term), meaning that a Condorcet winner will always win an Instant Bracket Voting election, because a Condorcet winner by definition is guaranteed to win each head-to-head match in the bracket-structured electoral competition, and this is true no matter what the seedings of all the candidates is.

This Ohio illustration involving Matt Dolan in both 2022 and 2024 exemplifies the transformation of Congress that could occur if all states, or Congress itself, were to employ Instant Bracket Voting for congressional elections. In race after race, voters would be able to elect the candidate whom they most prefer compared to each alternative one-on-one, instead of having the election end up a choice between a MAGA candidate and a Democrat when a majority would rather have had a non-MAGA Republican to either of those two. With Bracket Voting, Congress would be much less polarized than it currently is. Bracket Voting, like any Condorcet-consistent electoral method, would also enable the Senate to exercise its constitutionally essential role of serving as a check against an autocratic president—a role the Senate is currently unable to perform because Republican senators fear being primaried by Trump and thus can’t prevail in the November general election even if they would be Condorcet winners (a point I’ve made previously).

Bracket Voting Compared to Round-Robin Voting

Why is Bracket Voting better than any other Condorcet-consistent electoral method? All Condorcet-consistent methods elect Condorcet winners. Therefore, they all have the same beneficial property of counteracting polarization by electing the candidate closest to the electorate’s median voter (since the median voter is in the majority coalition that prefers the Condorcet winner to each opponent). Any Condorcet-consistent method, of which there are many, would safeguard America’s constitutional democracy from the threat of presidential despotism more effectively than any non-Condorcet method, like Instant Runoff Voting, which, as we have seen, risks replicating the same polarizing and democracy-threatening results as the prevailing electoral system of partisan primaries and plurality-winner (first-past-the-post) general elections. Given that all Condorcet-consistent methods share these key virtues, what is so special about Bracket Voting?

The answer lies in the distinction between bracket and round-robin tournaments that we examined at the outset. Bracket Voting, unlike some other Condorcet-consistent methods, needs no tiebreaker or backup rule to determine an election’s winner. The winner of a Bracket Voting election is determined solely by each round’s elimination procedure: in the case of four candidates, the procedure identifies who wins the two semifinals, and then who wins the final. (In theory, there could be a tie in a semifinal or final match. This is extraordinarily unlikely in a congressional election involving hundreds of thousands of votes.)

In a Round-Robin Voting election, all candidates have a head-to-head match against every other candidate, and the winner of the election is the candidate with the most head-to-head victories. Like Bracket Voting, Round-Robin Voting is Condorcet-consistent. A Condorcet winner, by definition, will win each head-to-head match against the other candidates, and thus will be the round-robin winner as the only undefeated candidate in the electoral tournament. Round-Robin Voting is arguably the purest form of a Condorcet-consistent electoral method, since the concept of a Condorcet winner is derived from what is essentially a round-robin tournament among the candidates.

But Round-Robin Voting needs a backup or tiebreaker rule. Not every election has a Condorcet winner, as Condorcet himself recognized. Moreover, in an election in which no candidate is undefeated in head-to-head matches, it is possible—indeed likely—that two or more candidates will be tied with the same highest number of head-to-head victories. In the case of a four-candidate Round-Robin election, if there is no Condorcet winner, then mathematically either two or three candidates must be tied with two head-to-head victories. (With four candidates, each candidate has three head-to-head matches for a total of six matches in the round-robin tournament, and if no candidate is undefeated with three head-to-head victories, then the total of six head-to-head victories must be distributed either as two victories for each of three candidates and one candidate with no victories or as two victories for each of two candidates and one victory for each of the other two candidates.)

There are various options for what the tiebreaker should be in Round-Robin Voting, with solid arguments in favor of several options. But all the complexity of needing a tiebreaker and debating which tiebreaker is best is avoided with Bracket Voting. Just conduct the bracket tournament among the candidates, and see who wins the final match after winning a semifinal (and any previous matches according to the structure of the bracket in the case of an election with more than four candidates).

Bracket Voting has the added advantage of being easily understood by any voter familiar with March Madness or any other tournament that uses the bracket structure, which means Bracket Voting is easily understood by most if not virtually all Americans. Voters need not know that Bracket Voting is Condorcet-consistent. They just need to consider Bracket Voting fair, as they surely will, for the same reason any bracket tournament is fair. As long as the seeding of the bracket is fair, then each match within the structure of the bracket is fair. There may be upsets along the way, as in March Madness, when a lower-seed beats a higher-seed, but that outcome is fair because it is the product of a fair head-to-head match between the two teams (or, in an election, two candidates).

If Instant Bracket Voting is used in a Final Four general election after a nonpartisan primary to determine the candidates who make it to the Final Four (as in Alaska), then it would be natural to seed the Final Four bracket based on the performance of the four candidates in the nonpartisan primary. If one is worried that voters might cast their Bracket Voting ballot strategically knowing the seeding of the candidates in advance based on the results of the nonpartisan primary—for example, a voter who wants the first-seed candidate to win and believes it would be better for the first-seed to face the second-seed in the final rather than the third-seed, even though the voter would actually prefer the third-seed over the second-seed, and thus votes for the second-seed to beat the third-seed in their semifinal—then the seeding of the bracket could be random and announced after voters cast ranked-choice ballots. But I doubt this kind of strategic voting would be much of a problem as it could easily backfire, and so I would introduce Bracket Voting to the public first with the most natural form of seeding and revise that part of the process later if necessary.

Let’s Use March Madness to Educate about Bracket Voting

As we watch March Madness unfold this year, we should seriously consider importing its basic format into the way we conduct our elections. Our current electoral system is risking the complete demise of democracy in America. We desperately need to try something new. As a Condorcet-consistent electoral method, Bracket Voting is designed to counteract the polarization that is causing such problems and, most importantly, to avoid the election of extreme authoritarians who are not Condorcet winners but prevail because the current system blocks Condorcet winners from demonstrating that a majority of voters prefer them to each of their opponents.

Bracket Voting is the Condorcet-consistent electoral method with features most familiar and intuitive to American voters. Therefore, Bracket Voting is the Condorcet-consistent method most likely to be adopted in the near future by states, like Ohio, that permit voters to reform the electoral process through a ballot initiative. Unless new evidence emerges that some other form of Condorcet-consistent voting would be easier to adopt, we ought to move as quickly as possible to educate voters about the possibility of Bracket Voting and why it is advantageous compared to the current system. Now, when Americans are focused on March Madness, is a good time to begin this work.

Okay, Ned, thank you for writing this. Specifically:

"The ballot in an Instant Bracket Voting election could look the same as ballots in any Ranked-Choice Voting election. The voters would rank the candidates in order of preference, ..."

We must make it clear that, in this case, this *is* a form of Ranked-Choice Voting and not allow FairVote to appropriate the umbrella term to mean only Instant-Runoff Voting. Personally, I think that's the *only* way Instant Bracket Voting can be done. Expecting voters who never ever think about March Madness or athletic tournaments to fill out brackets on their ballot is not going to fly. Not in my opinion. It has to be a ranked-ballot, RCV. (But not IRV.)

But then the question I have is this: We know that this is Condorcet-consistent, so we know that no matter how it's seeded, if there is a Condorcet winner (which is 99% of the time) that Condorcet winner will be elected. But if there is *no* Condorcet winner, the outcome of the election will depend on how the first round is seeded. That's a problem. The method should be deterministic and not depend at all on a random manner of who gets matched up with whom.

That's why I think that Round Robin (or what I might call "straight-ahead Condorcet") is fairer and clearer than Instant Bracket Voting. And if there *is* a cycle, it's not exactly a tie unless the votes were perfectly symmetrical between the candidates involved in the cycle (the Smith set).

Consider a Round-Robin Tournament that ends up lacking a Condorcet winner. If it were hockey or basketball or wrestling, they could do as Nic Tideman suggests and favor the matches with scores having wider margins over the matches with smaller margins as a basis for identifying the champion. Or Minimax.

Two years ago, I was able to get a Vermont legislator and counsel to write a Condorcet RCV bill and we were considering Bottom Two Runoff IRV vs. a straight-ahead Condorcet (with Plurality for the contingency that there is no Condorcet winner). https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2024/Docs/BILLS/H-0424/H-0424%20As%20Introduced.pdf

The BTR-IRV was attractive because it is the smallest modification to Hare IRV that makes IRV Condorcet-consistent and the modification is easily understood, It's also a Single-method Condorcet system. It just does what it does and someone is elected. If there is a Condorcet winner, that candidate will be elected. If there isn't, someone is still elected with this single method.

The reason we settled on a Two-method Condorcet system was because this legislator, the legislative counsel, and I all agreed that "The law should say what it means and mean what it says."

It seemed that straight-ahead Round Robin, with language to meaningfully resolve a cycle, would be easiest for everyone to understand and to buy into it. If there ever was a cycle, most people would accept the resolution of the cycle as fair. If I were to do it again (and we might do it again this session, I dunno), I think it would be Condorcet-TTR for top-two runoff instead of Condorcet-Plurality. That would make it elect the Hare IRV winner in the case of a cycle involving just the top three candidates.

But I'm a little nervous about this Instant Bracket Voting if there is a Condorcet cycle and the outcome depends on how the candidates are seeded. It shouldn't.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.03455

RSEB has some strategy-resistance properties, too (though I don't claim to understand them)