A Must-Read Analysis of Why U.S. Elections Aren't Working and What to Do About It

If you read one thing about the structural problem afflicting American elections, including an explanation of the institutional reform most likely to remedy the problem, make it this new analysis.

Every once in a while you read something and say, “Wow, that’s fantastic!”

That was my reaction to reading a new paper by Nate Atkinson and Scott Ganz.

Disclosure: I am fortunate to join Nate and Scott as a co-author on a separate paper that relies on their analysis of the varying degrees of partisan polarization in all 50 states and its implications for electoral reform.

But this new paper, which is a separate endeavor on their part, is truly something extra special.

What’s so great about it? At least two things.

First and foremost, it supplies an account of electoral competition that persuasively explains—far better than anything else I’ve seen—why the current existing electoral system of partisan primaries and “first past the post” (plurality winner) general elections cannot handle the increasing amount of partisan polarization that has developed in American politics. Second, it examines new data relating to congressional elections that show how the existing electoral system exacerbates the degree of polarization among voters.

I will explore both these key points a bit more.

The Model of Electoral Competition

One of the most famous works in political science is Anthony Downs’s explanation of how electoral competition in a first-past-the-post (plurality winner) system will cause two relatively moderate political parties, one on the left and the other on the right, to pursue center-oriented agendas in their efforts to appeal to the electorate’s median voter.

It has become increasingly clear, that Downs’s analysis does not explain what is currently occurring in the United States as elected representatives move further and further from the median voter. Whether or not the voters themselves are becoming as polarized as the partisan politicians who represent them, the officeholders undoubtedly have become sharply polarized in terms of their partisan animosity towards the opposite side.

What accounts for the failure of Downs to explain the current nature of electoral competition when his explanation seemed to make so much sense 66 years ago, when he published An Economic Theory of Democracy?

Nate and Scott supply the answer by digging into the dynamics of competitive forces among candidates. Trained at Stanford Business School, where they both received their PhDs, they use their understanding of market forces to illuminate how a lack of competitive pressure in a two-party system with partisan primaries leads to the polarization of elected representatives. As part of justifying their use of economics to study the electoral system, they cite the influential paper by Sam Issacharoff and Rick Pildes, Politics as Markets, which was honored with a twenty-fifth anniversary symposium on the Election Law Blog. I would venture to say that Nate and Scott’s new paper is the most significance invocation of the Politics as Markets framework since that paper was published a quarter-century ago.

Nate and Scott’s key insight is that when one party chooses not to cater so closely to the preferences to the electorate’s median voter, that reduces the incentive for the other party to do the same. As long as the opposing party stays closer to the median voter than the first party, the opposing party doesn’t need to stay especially close. Thus, when one party strays, so can the other without losing voter appeal, as long as it doesn’t stray as much.

Nate and Scott root their analysis in the basic point that candidates have ideological and electorate incentives that can conflict. If a candidate’s own policy views diverge from the median voter’s, the candidate will want to move towards the median voter in an effort to get elected. Conversely, however, the candidate will want to resist moving closer to the median voter, insofar as the candidate still has a chance of winning while doing so, because of the candidate’s own preferences. As polarization starts to seep into politics, a vicious cycle starts where candidates try more and more to diverge from the median voter and still get elected.

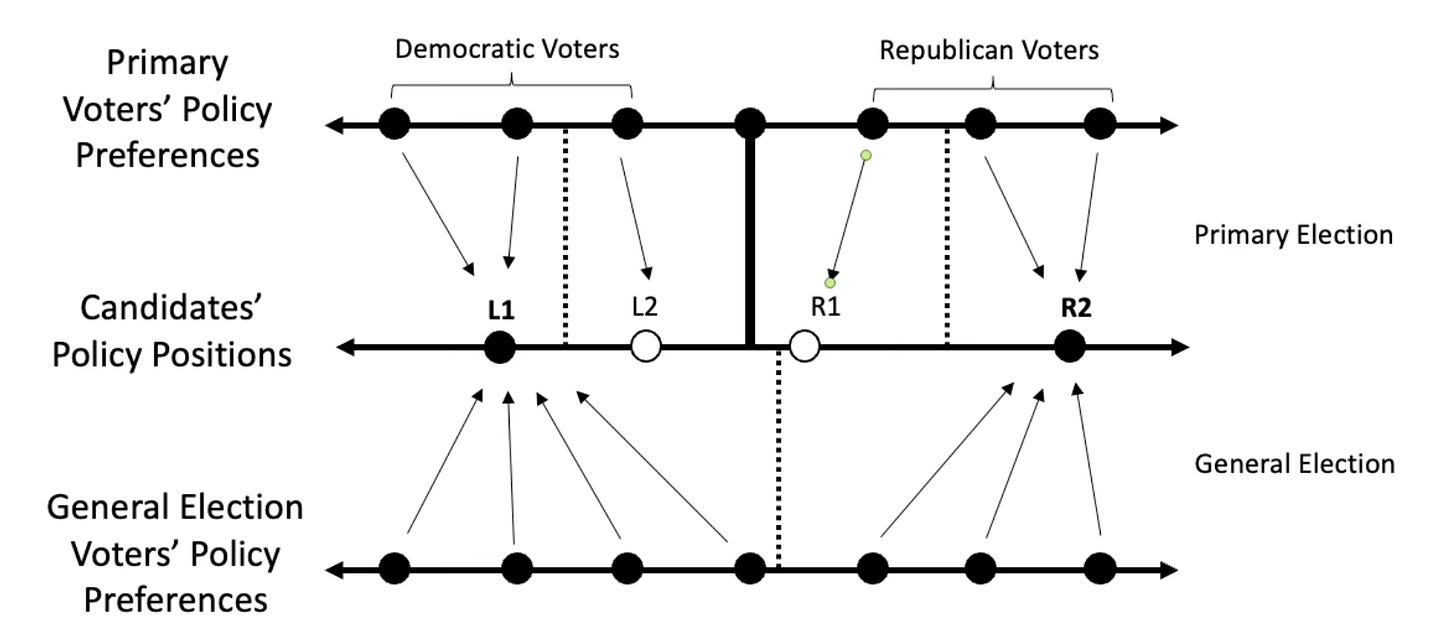

Their paper shows how partisan primaries exacerbate this problem. A candidate needs to win a partisan primary before winning the general election. Insofar as voters in partisan primaries are more partisan than voters in the general election—the “blue” and “red” primaries attract “blue” and “red” voters, resulting in fewer “purple” voters in the two major-party primaries combined (as a percentage of total primary voters) than in the general election (as a percentage of all voters)—candidates competing in the primary will need to win the support of the median “blue” or “red” voter, depending on which party’s primary they run in. They won’t necessarily need to tack very far towards the purple center in the general election if the opposing party’s nominee also isn’t tacking back very far.

Nate and Scott provide a useful illustration of this dynamic:

The winners of the primaries defeat candidates whom the median voter in the general election would have preferred to each of the primary winners. Nate and Scott summarize the point this way: “Candidates close to the median voter in the general electorate may be far from the median voter in a partisan primary. Similarly, candidates who are close to the median voter in a partisan primary may be far from the median in the general electorate. And, if one party uses a partisan primary to select their candidate and it appears that electability is a secondary concern for the primary voters, this weakens the incentive for its rival party to pressure voters to select an ‘electable’ candidate.”

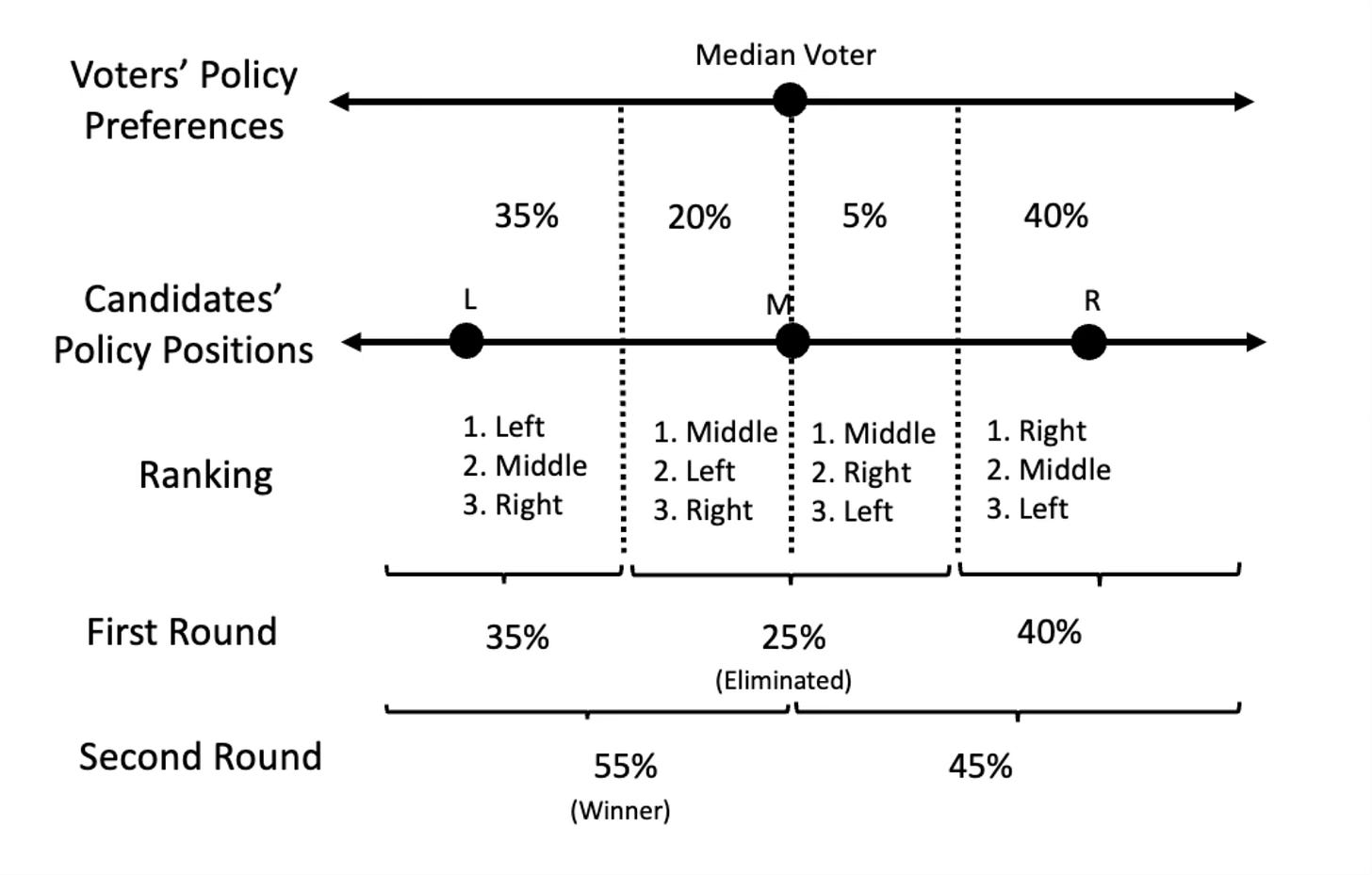

Nate and Scott use the same theoretical framework to show why the version of Ranked Choice Voting used in Alaska (and elsewhere) cannot remedy the problem of hyper-polarization. A “purple” candidate close to the median voter, but with very little enthusiastic support among the polarized voters, will be eliminated by the “instant runoff” procedure employed in Alaska’s RCV system, leaving the election to be decided by relatively extreme “blue” and “red” candidates—just as in the case on an election with partisan primaries and a plurality-winner general election. Again, they helpfully illustrate the point:

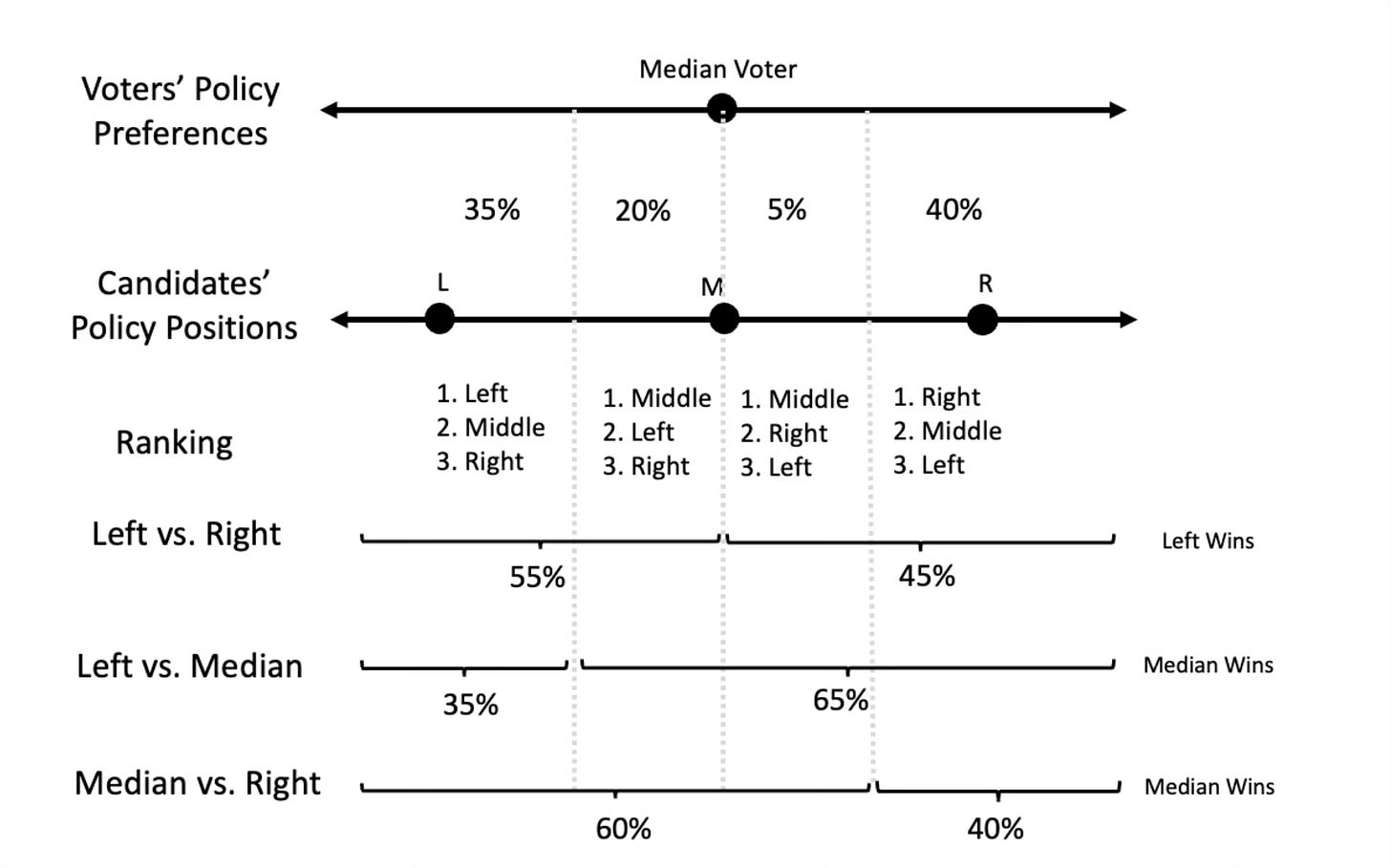

Only a “Condorcet-consistent” electoral system can counteract the hyper-polarization that is impervious to Alaska’s version of RCV. A “Condorcet-consistent” electoral system is the kind pursued here at Common Ground Democracy. Named after the Marquis de Condorcet, the eighteenth-century French thinker who developed the method, a “Condorcet-consistent” electoral procedure elects a candidate whom a majority of voters prefer over each other candidate when compared one-on-one. This majority-preferred candidate is a “Condorcet winner,” and mathematically is always the candidate closest to the electorate’s median voter. Thus, with respect to the same set of preferences that results in the defeat of the “Condorcet winner” if Alaska’s RCV method is used, a “Condorcet-consistent” version of RCV (of which there are many) will by contrast elect the “purple” candidate, as Nate and Scott show in another one of their illustrations:

Drawing upon their understanding of competitive incentives, Nate and Scott observe that a Condorcet-consistent system doesn’t necessarily need to induce a third purple candidate into the race. Rather, the mere possibility of entry by a purple candidate in a Condorcet-consistent system forces the blue and red candidates back towards the median voter in a way that neither the existing system nor Alaska’s is able to do. As Nate and Scott put the point, “the very threat of entry by an electorally motivated candidate keeps the major party candidates disciplined in a way that they are not under either plurality or IRV.”

New Congressional Data

In addition to providing their persuasive model of electoral competition under conditions of polarization, Nate and Scott also provide new empirical evidence of the degree to which congressional polarization has outpaced electorate polarization in recent years. Taking two different data sets, they compare the ideological divergence among voters with the ideological divergences among elected members of Congress. Their analysis shows that “the elected representatives are becoming more extreme at a faster rate than the electorates they represent.”

The combination of the model and data that the paper presents is a strong reason for states, especially those with the most polarized electorates, to consider moving to a Condorcet-consistent system. The “top three” system that I have discussed recently here at Common Ground Democracy, applicable both to congressional and presidential elections, is one such system—and has the added advantage of not requiring ranked ballots for those states opposed to any form of RCV. But for states willing to use RCV, there are a variety of Condorcet-consistent options to consider.

To be clear, I am so enthusiastic about Nate and Scott’s paper not because I’m already a proponent of Condorcet-consistent methods and their analysis confirms my previous beliefs. On the contrary, when in 2021 I began my inquiry into what electoral system would best address the problem of increasing partisan polarization, I was expecting that Alaska’s system would suffice as an already existing “off the shelf” solution. And, indeed, as Nate and Scott themselves observe as part of their analysis, the Alaska system works reasonably well when the electorate is not polarized. But, as I examined how Alaska’s system might operate in a state like Ohio, I realized that it was not strong enough medicine to cure the degree of polarization that had already occurred. Only Condorcet-consistent methods are capable of doing that.

What impresses me so about Nate and Scott’s paper is not the conclusions it reaches. Rather, it is the clarity and sophistication of the analysis it uses to reach its conclusions, along with the supporting empirical evidence it provides.

Anyone wishing to understand what is currently ailing American politics, and how best to remedy this ailment, can’t do any better than to start by reading this new piece.

Hi Ned, you and your colleagues are misreading Anthony Downs when you write "It has become increasingly clear, that Downs’s analysis does not explain what is currently occurring in the United States as elected representatives move further and further from the median voter." Downs's FULL analysis actually explains it quite well. But the strip-mined version that most political scientists use to justify their own work is not really Downs's work. Specifically you and others apparently have forgotten that Downs had proposed an important exception to his well-known "median voter" analysis: what if, he asked, the distribution of voters is not humped in the middle of the ideological spatial market? What if instead the electorate is polarized? In that case, Downs showed, the two parties will “diverge toward the extremes rather than converge on the center. Each party gains more votes by moving toward a radical position than it loses in the center.” When the electorate is polarized, Downs’ model portrayed the distribution of voters as two-humps, equal in size, like a Bactrian camel’s back.

In such a situation, Downs goes on to predict that “regardless of which party is in office, half the electorate always feels that the other half is imposing policies upon it that are strongly repugnant to it.” But in addition, Downs wrote "In this situation, if one party keeps getting reelected, the disgruntled supporters of the other party will probably revolt; whereas if the two parties alternate in office, social chaos occurs, because government policy keeps changing from one extreme to the other.” Thus, Downs concluded, the two party system “does not lead to effective, stable government when the electorate is polarized.” These predictions look presciently familiar when observing US politics today, as many diehard supporters of both the Democrats and Republicans are convinced that the other side is tantamount to evil.

In the ensuing six decades following Downs’ pivotal work, political scientists, editors, pundits, politicos, academic researchers, even a Supreme Court justice (Scalia) selectively strip mined Downs for their own purposes. These neo-Downsians ignored those parts of the Downs model that apparently did not fit in with their preferred vision of America as a nicely-organized, centrist, single-humped electorate. Thus, Downs’ formulation of what happens to a democracy when the electorate is polarized into two voter distribution humps somehow was left on the cutting room floor.

What remained was a half-baked simulacrum of the Downs theory, and the two-party system transmogrified in many minds into a proxy for moderate, majoritarian, centrist government. Down’s median voter acquired a reputation as a political moderate. And the policy passed by that government was presumed to be preferred by a majority of voters. But in fact Downs never did declare that, unequivocally, he always put conditions around it. You might find this short article instructive: "Faulty Textbooks: The Strip Mining of Anthony Downs’ "Economic Theory of Democracy" https://democracysos.substack.com/p/faulty-textbooks-the-strip-mining

This is called the "center-squeeze effect".